This was originally published back in 2017.

The Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal 京杭大运河 Běi háng dà yùnhé is the longest artificial waterway in the world, and it has retained that title for thousands of years. This canal is rich with history, and it passes through Changzhou. Like natural rivers, it has many off shoots and “tributaries.” One of these passes through the city center. As far as I can tell, this section is called 城河 Chéng hé, but I have seen that name used only once and in Chinese on a sign downtown. It literally means “City River,” so I am going to assume that is its name in English. I thought it might be interesting to follow this narrow canal from where it begins to where it ends.

We start at Yanling Road on the edge of downtown. There is a point where it looks like the canal forks at Dongpo Park. This is deceiving. This part of the park is actually an island and the canal flows around it.

The fork happens behind the “mainland” part of Dongpo Park. Truth be told, this part is not as picturesque. To the right in the above photo, you can see the curved roof corner of the gatehouse. This, essentially, blocks off City River from the main canal. So, presently, people cannot get boats onto this narrow waterway.

For a good bit, City River parallels Yanling Road. It passes under this bridge and pavilion — which features a statue of two guys playing Chinese chess.

It continues on as it passes in front of Hongmei Park and the entrance to Tianning Temple. Then, right before Wenhuagong — where they are building the downtown subway station — it veers away of Yanling.

To maintain eye contact with the water, I had to leave Yanling and follow Chungui Road. This is basically a street that runs in front of a residential buildings, so there isn’t much to see here.

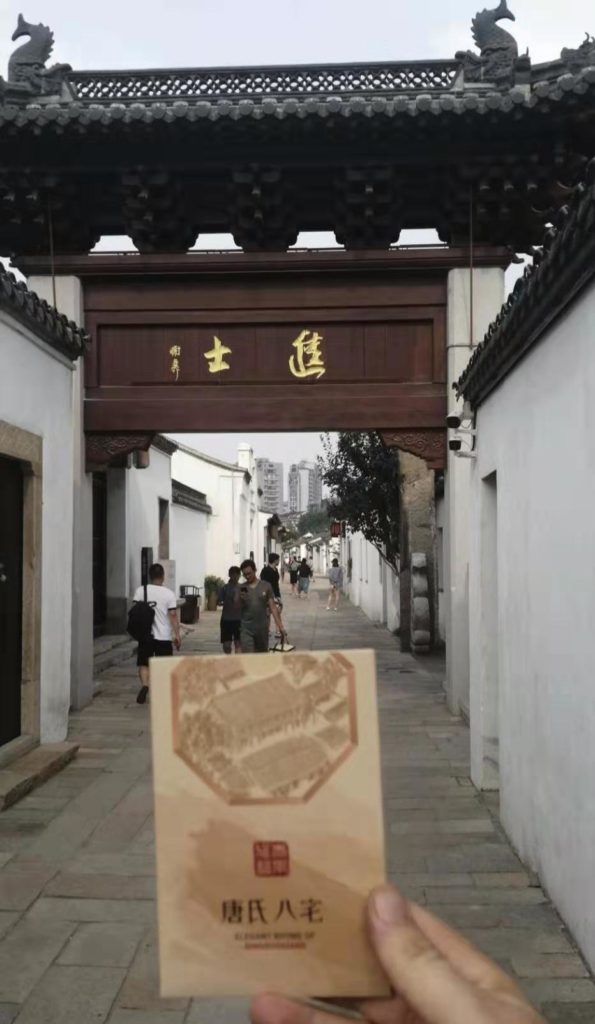

City River eventually flows under Heping Road near a big Agricultural Bank of China branch office. I used to wonder why this bridge was here. Basically, it’s much, much older than Heping itself, and the street had to be built over the canal. This bridge faces Qingguo Lane, but that alley is shut off due to it being renovated into a historical district.

You can tell Qingguo is undergoing massive restoration because, simply put, the houses on the right do not look as run down and dilapidated as they did years ago. It was from this point on I realized why this tiny waterway was dug in the first place.

The renovation bit can’t be said for the other part of Qingguo that is more residential, but the thought I had remained unchanged. China has a lot of canals. If you think about it, they were a necessity a thousand years ago. Since these are artificial rivers, there really are no tides or currents when compared to something like the Yangtze. It makes traveling by boat in between cities easier than using horses and traveling over land. This is especially important if you are trying to transport cargo from one city to the next. This is why you still see barges using the canals to this very day. Not only are these canals ancient, but they still have a practical use.

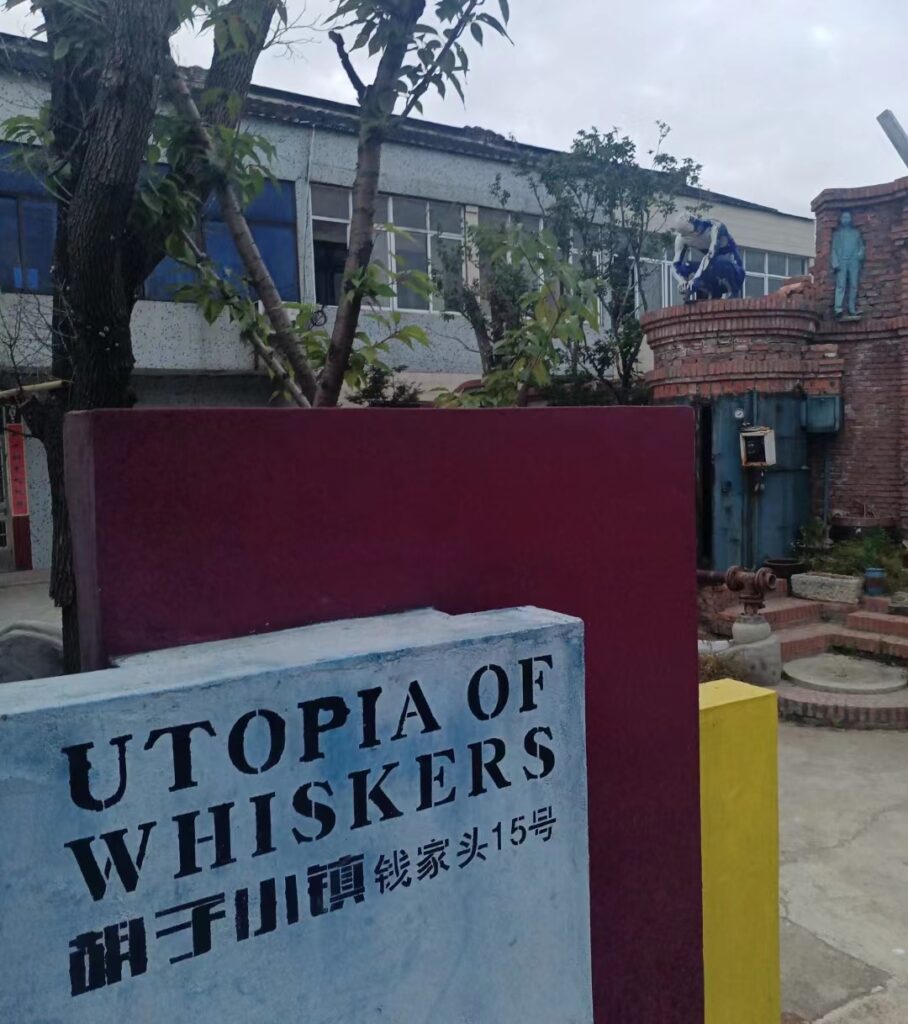

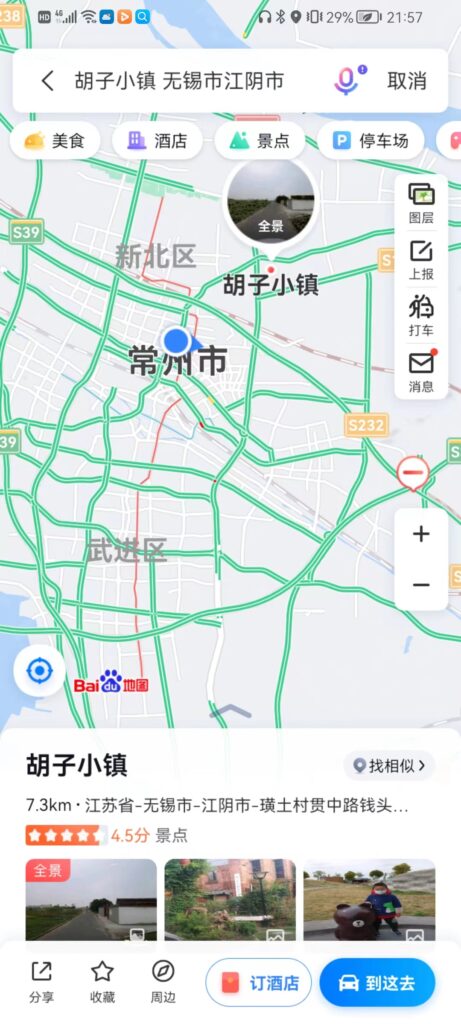

Okay, that explains the practicality of The Grand Canal, but why does City River exist? Qingguo Lane is where a many, many historical figures in Changzhou once lived. The above photo is the part of the canal that runs past Nandajie, Laimeng, and Bar Street. This canal, and the other small ones like it, allowed the citizens of ancient Changzhou easy access to the main body of water. So, eons ago, if you were wealthy and influential, you likely wanted to live near the canal. You would have had quick and easy access to what was, back then, the mass transit system.

City River ends at what is called, in English, the West Gate. This is near the city boundary wall dating back to the Ming Dynasty. It’s also near the west entrance to Laimeng — the area where there is a lot of restaurants on the second floor. It’s also not that far from Injoy Plaza. This gatehouse also blocks access to this canal. So, in that way, its preserved, and you will likely never actually see a private boat traveling this waterway.

If this were a bygone era, this is where you would see vessals from City River getting onto the canal proper. If you head west, you would end up in Zhenjiang. East would take you to Wuxi, which like Changzhou, has it’s own network of small canals branching off the main one in its city center. What I have learned, recently, is that if you want to understand the ancient history of a town — whether it’s Zhenjiang, Hangzhou, Suzhou, Wuxi, or even Changzhou, you have to understand why the canals were excavated in the first place. I also realized that if you’re going to go aimlessly wandering looking history and culture, one way is to just follow the path of the canal.