This was originally published in 2017.

Who says my heart of a grass seedling

Can ever repay her warm spring sun?

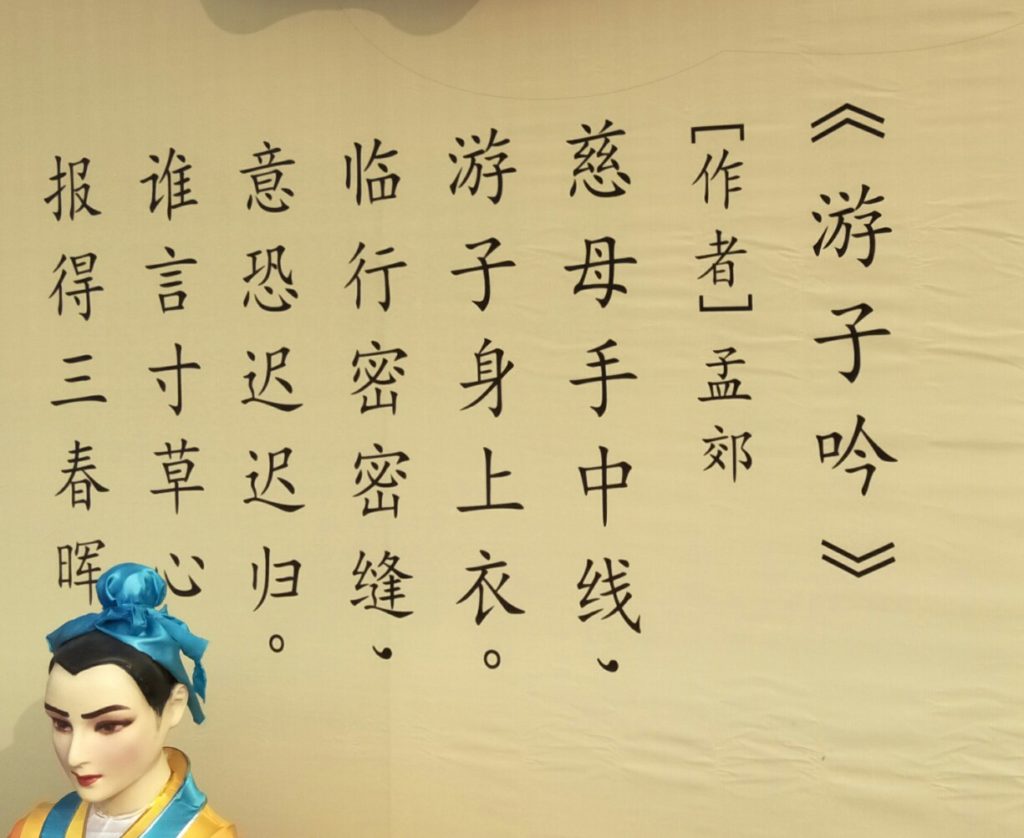

–Meng Jiao, from Traveler’s Song

Meng Jiao 孟郊 clearly loved and cared for his mother. The above lines — taken from this translation of “A Traveler’s Song” — convey that as do the rest of the poem. For a large part of his life, he refused to take the imperial exams, but he eventually relented once he reached middle age. A civil service job, he reasoned, would allow him to financially support her as she grew older. This eventually led him to a ministerial position in Liyang — a city to the south that is part of Changzhou’s prefecture. There, he dithered around among streams and forests while composing poems.

“A Traveler’s Song” (遊子吟) was one of those poems he wrote while living in Liyang. It’s a short bit of a verse. It speaks of a son about to set off to travel, and his mom is sewing his clothing for him before he leaves. The poem doesn’t mention where the son is going or how long he will be gone. It’s just the departure is impending, and that both the son and the mother will miss each other.

Generality can be a blessing and a curse in poetry. It largely depends on the linguistic skill of the poet in conveying emotion. This poem, in the variety of English language translations I have read, uses generality and vagueness rather well. It gives a reader just enough information while allowing them to read their own life into the lines.

For example, Meng Jiao’s poem remind me of my own mom. While I was in college in West Virginia, my parents still lived overseas — The Netherlands for a year, and then the UK until my father retired from the US Department of Defense. I came to visit for a few weeks every Christmas and New Years. Eventually, I would have to get back on the airplane and fly across the Atlantic. I wouldn’t see them again until summer, when they would come to the US to see my brother, sister, and myself. There was always talk of time and distance every time my Mom and I parted ways. Of course, plenty of other readers around China and the rest of the world have had no problem understanding this poem. It is one of Meng Jiao’s most famous works.

It is always interesting to see how a famous piece of literature transcends written text and takes on a life out in the world. “A Traveler’s Tale” is actually part of the decorative lanterns at Dinosaur Park in Xinbei. A large chunk of the colorful art on display have more generalized holiday themes. However, there is a portion close to Hehai Road that recreates Changzhou history.

I found this recently because a friend and I went on a stroll specifically to look at the lanterns and laugh at their gaudy silliness. We both sort of stopped and lingered at the Meng Jiao display, because, well, part of it looked a little creepy.

At the time, we both didn’t know what we were looking at. The reddish marks on her face look a little like bruises. I didn’t quite know what to make about the black smudges around the both eyes. Now that I have had time to think about it, it’s the limitations of the medium when it comes to this sort of public art. Spring Festival lanterns easily look childish. The vibrant, bright colors have something to do with that. However, if you look at Meng Jiao’s mom, and the nearby recreation of Su Dongpo, they have a difficulty in conveying age.

Of course, I am nit picking. The point Spring Festival lantern displays is to do exactly what my friend and I did — walk around and smile at them. There is plenty of time to do just that. While the western holiday season is coming to an end, the run up to Spring Festival is just beginning.