In the Changzhou prefecture, how many train stations are there?

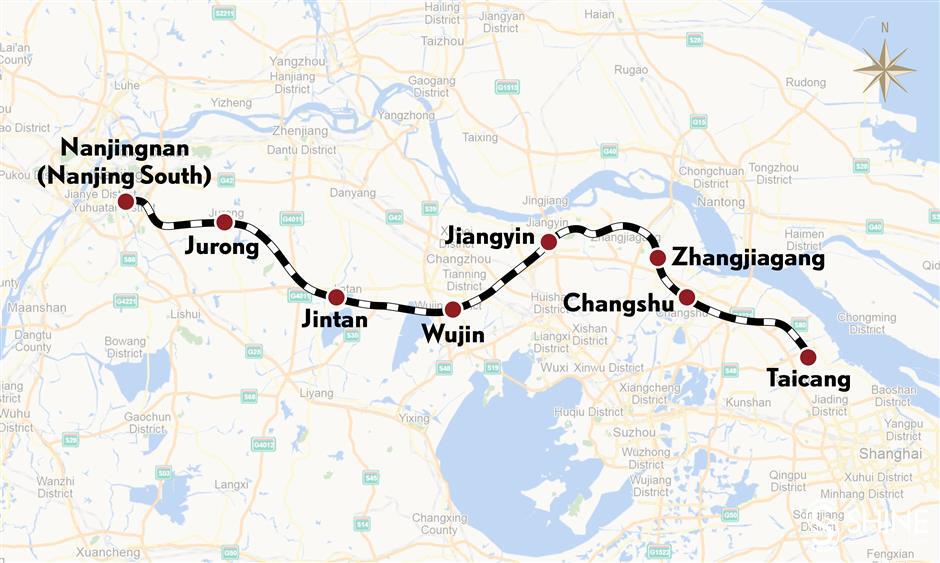

This question was part of a bar trivia quiz I wrote a and hosted a couple of years back. Most people got the answer wrong. Because of the word “prefecture,” you have to include the city of Liyang into the count. Funny thing about that: it’s on a line to Nanjing, but there is no direct link between the municipalities of Liyang and Changzhou. So, back then, if you made a list of all the stations, it would be: Changzhou (downtown), Changzhou North (Xinbei), Qishuyan, and Liyang. Well, that was years ago, but recently the number four became incorrect.

The number of high speed rail stations in Changzhou is currently six. Wujin got a brand spanking new station.

As did Jintan. They are part of a new railway line that opened this year.

Technically, this map is not right. The terminal station isn’t Taicang, Suzhou prefecture. Actually, Shanghai is the most common final stop.

I have taken an active interest in this new high speed line for one particular reason. The university I teach for moved its Changzhou campus from Xinbei to Jintan. Myself and other Hohai employees knew this was coming for years, and fall semester, 2023 is when it finally happened. I was confronted with a choice: either move to Jintan or commute.

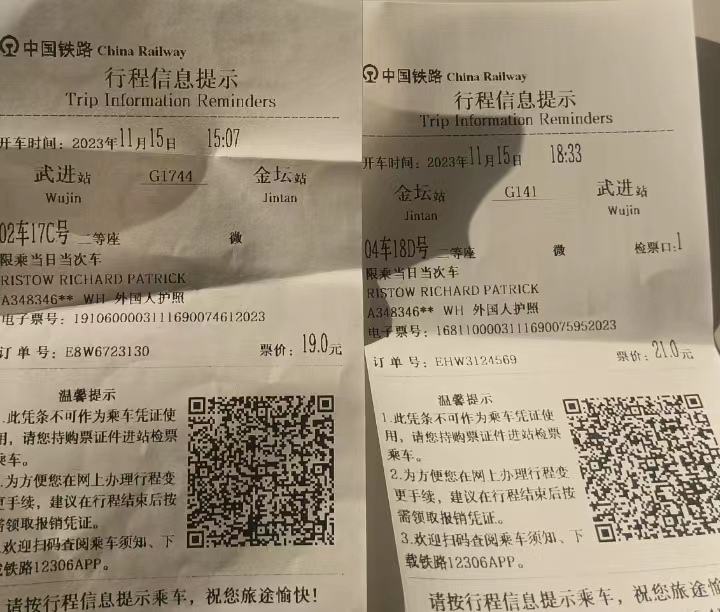

I absolutely didn’t want to leave where I currently live in Tianning, Without divulging too much personal information, I didn’t want to uproot myself from personal relationships and friendships that took years to cultivate. I knew the rail line was coming, and I had this romantic notion that I could take the train every time I needed to go teach classes. And I could do that while playing games on my Nintendo Switch! So, on a recent day off, I decided to actually test that potential commute by taking a train from Wujin to Jintan and back.

For the most part, this leg of the route actually parallels the toll highway one would take if driving from Changzhou to Nanjing’s international airport.

Out the other side of the train, there is a view of the Xitaihu community on the north side of Ge Lake that zipped by. All in all, the ride from Wujin was a little over ten minutes.

So, it wasn’t long before I saw the newly familiar sight of my university’s new campus. It was only like a 10 to 12 minute ride. So, the question is this: is taking a train from Wujin to Jintan worthwhile if you got business to be done in Changzhou’s western most district?

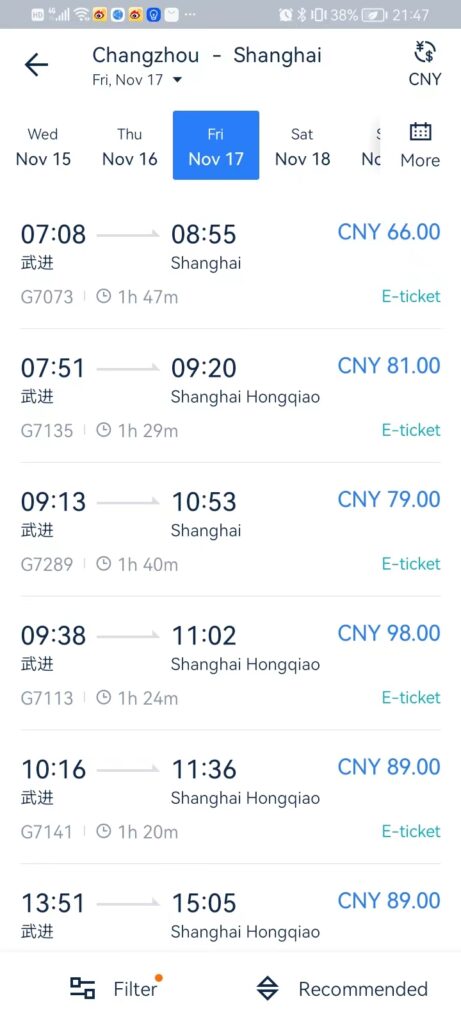

The answer is simply no. It maybe a 2 RMB price difference but travelling to Jintan from Wujin is cheaper than the other way around. I asked a friend of mine who is a huge train, architecture, and infrastructure nerd how this could be. He answered simply: lesser frequented stations will actually charge a little bit more. In short, in the journey from Shanghai to Nanjing on this line, the train stops more in Wujin than it does Jintan. I certainly saw this first hand because I tried to buy a return ticket as soon as I arrived. I had to wait three hours for the next departing train. I did that, and while doing so I saw a lot of trains blowing through the district and not stopping.

The train station is actually in the middle of nowhere. I’d estimate that Jintan’s downtown area and Hohai University on the northern banks of Changdang Lake 长荡湖 are ten minutes drive by car. Add additional commute time if you are hailing and waiting for a car or taxi to pick you up. A traveler can take a public bus from here to other parts of the district. However, it’s a well known fact that public busses go a lot slower than cars. Collectively thinking about all of that, it’s easy to conclude that taking the train to Jintan for a day trip or commuting to work is not exactly convenient. This is especially true since the primary employer of foreigners in this part of Changzhou is a German industrial park, but that is actually an exit on the Jinwu Expressway connecting Jintan to Wujin.

Simply, put: travelling by car to Jintan is still the most time efficient and convenient way to get to this part of the city. So, once the three hours were over and I was finally on my way back to Wujin’s station and its subway stop, I realized that playing my Nintendo Switch going to and from work was a wholly unrealistic fantasy.