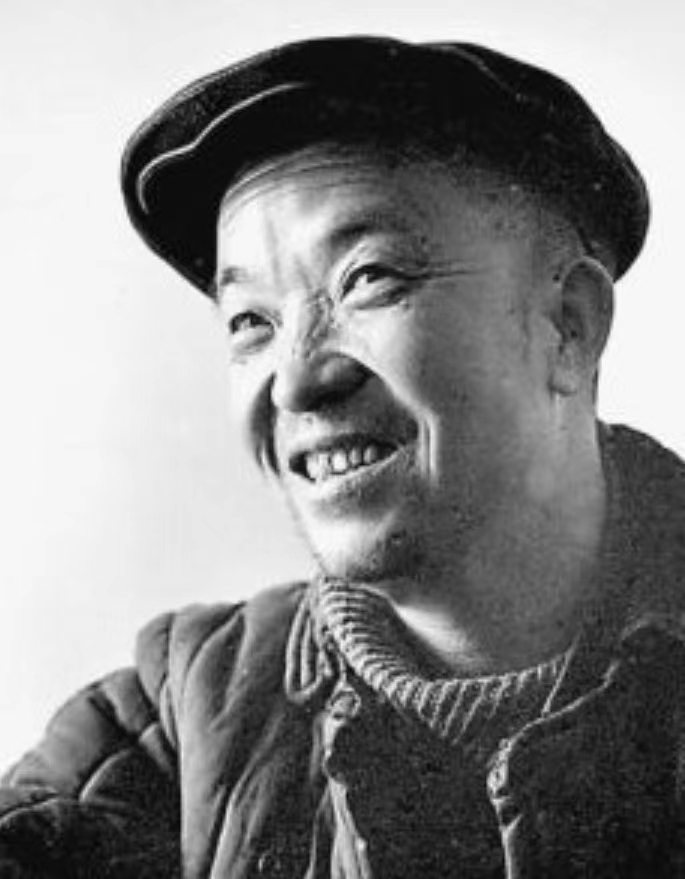

China used to have “model worker” and “learn from …” promotional campaigns. Essentially, these were propaganda initiatives trying to instill the values of civic duty, patriotism, and hard work into the population. Lei Feng, pictured above, is perhaps the most enduring. Back in the 1960s, there were others.

Wang Jinxi is one of them, and decades ago he also got the “iconic” treatment. Lei Feng was a People’s Liberation Army soldier that died young when a telegram pole fell on him. Wang wasn’t a soldier; he was an oil field worker.

The characters 工业学大庆 gōngyè xué dàqìng means “Learn from Daqing Industry.” Daqing is a prefecture-level city in Heilongjiang province in north east China. This is a part of the country that shares a border with Russia. In the late 1950s, prospectors found a large oil field there. In the 1960s, Mao and other members of the central government announced a “massive battle” to open up Daqing for drilling. China desperately wanted petroleum independence and reduce it’s dependency on imports to satisfy energy needs.

Wang Jinxi was tasked to lead the drilling team. According to the story, he and his intrepid squad toiled in temperatures well below zero degree Celsius. Their dedication faced constant issues of fatigue and injury, and yet they soldiered on. Wang’s dedication to hard work earned him the nickname of “Iron Man.” But, not in a Tony Stark / MCU / Marvel Comics sense. One story involves Wang personally throwing himself into a mud pit to clog up a “blowout hole.”

Apparently, doing this didn’t kill him. He died decades later, of cancer. Wang is also hailed from Gansu province, and he is remembered for work in Heilongjiang. Jiangsu and Changzhou is no where near this historical conversation. So, that begs a question. Why is this being written about on this blog?

I found a statue of him in Tianning — just down the road from Changzhou’s central train station. I was driving a car, and I had just dropped off a friend for a business meeting. I needed to kill sometime before picking her back up. So, I thought it might be good to fill up the gas tank.

The statue is placed at a gas station. Given the story behind the guy, it’s actually more logical than a random tank and a couple of missiles on display at a Xinbei gas station.

Oil and natural gas are still being extracted from Daqing to this day. However, peak production has already occurred many, many years ago. Wang Jinxi’s old oil field is currently in decline. As for Mao’s drive for oil independence, that really never came about. China currently is the biggest importer of crude in the world, with Saudi Arabia being the biggest provider.