This post was originally published in July. 2018

“I am into philately,” my father once said. “I like to philatellate.”

I squinted my eyes at him, sternly. ”You like to whip people?”

“No.” He rolled his eyes. “Rich, that’s flagellate.”

“Oh, got you,” I said. “So, you are a philatellator!”

He sighed. “What is wrong with you? The right word is philatelist.” He pointed at me. “And furthermore…”

“Oh, who cares?” My mom interjected. She looked at my dad. “A grown man obsessed with stickers! Besides, I’ve had to listen to you two invent new gibberish words all dinner.”

“They’re postage stamps, not …”

“Paul, you are talking about little pieces of paper with glue on the back.” She took a sip of her Diet Coke. “I pass out stuff like that to my students when they do well on tests or behave themselves.”

“Jeez, I can’t win for trying.” My father stood from the dinner table. “You know, I am going to go to my office right now and philatellate some.”

And by that, he went to go play with his stamps. It’s hobby that has engrossed my dad for his entire lifetime. Given the international scope of his career with the US federal government, his extremely large collection spans the entire globe. The above conversation happened when I was a senior in high school. On and off, I have always talked about stamps with him, and it seems I am the only of his three kids that was remotely interested in doing so. Ever since I moved to China, I thought it was only fitting that I help round out his collection.

Recently, I sought out some new Chinese stamps for him, but not because I am a dutiful son. Actually, I can be quite a moron, and recently, that was most definitely the case. Because of a recently planned trip to Buffalo, my father took me to JFK International in New York City in a rental car. After he dropped me off and left, I realized that I still had his regular car keys. Basically, I accidentally stole his regular house keys and had no way to get them back to him — other than mailing them express from Changzhou once I returned. Essentially, I screwed up royally, and there is no way to really say “I’m sorry” to someone than to give them something that genuinely excites them. For my dad, that’s stamps.

So, that brings up a question. If you are a stamp collector and you live in Changzhou, how do you go about adding to your collection? China does not have stamp stores the same way America and Europe does. The first option is to go to an antique market.

There are a few scattered across the city. One of the biggest ones — across from Hongmei Park — recently got bulldozed. So, the defacto go-to place is now behind the Christian church downtown. However, there are challenges when shopping at places like this.

There is the issue of the language barrier, but that can be fixed by having a Chinese friend tag along. Antique markets are usually better for experienced collectors, and this is a place where you can find old themed albums or issues from years ago. In short, not only do you need to be able to communicate, but you also need to know what you are looking for. There is another option for those who are wading into Chinese philately for the first time. It’s the actual Postal Bank of China.

This is a place where you can not only buy stamps, mail letters, and ship packages, but you can also open a savings or checking account. It’s both a post office and a bank. However, the branch offices scattered throughout the city are not really suited for stamp collectors. There is only one place that actually geared toward philatelists. Its English name says it all.

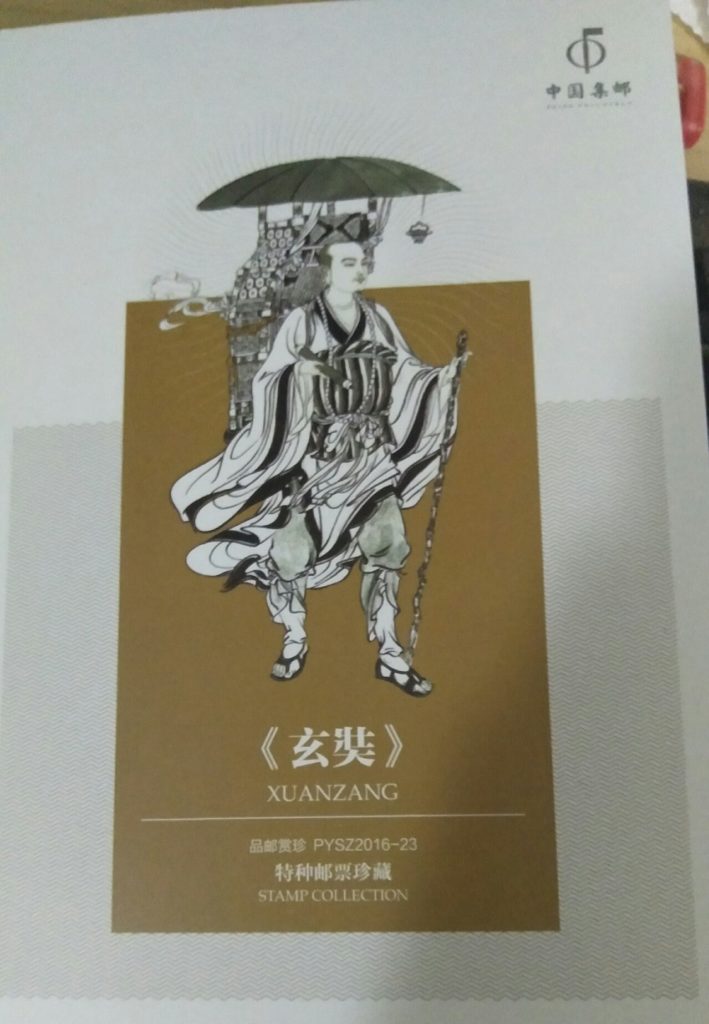

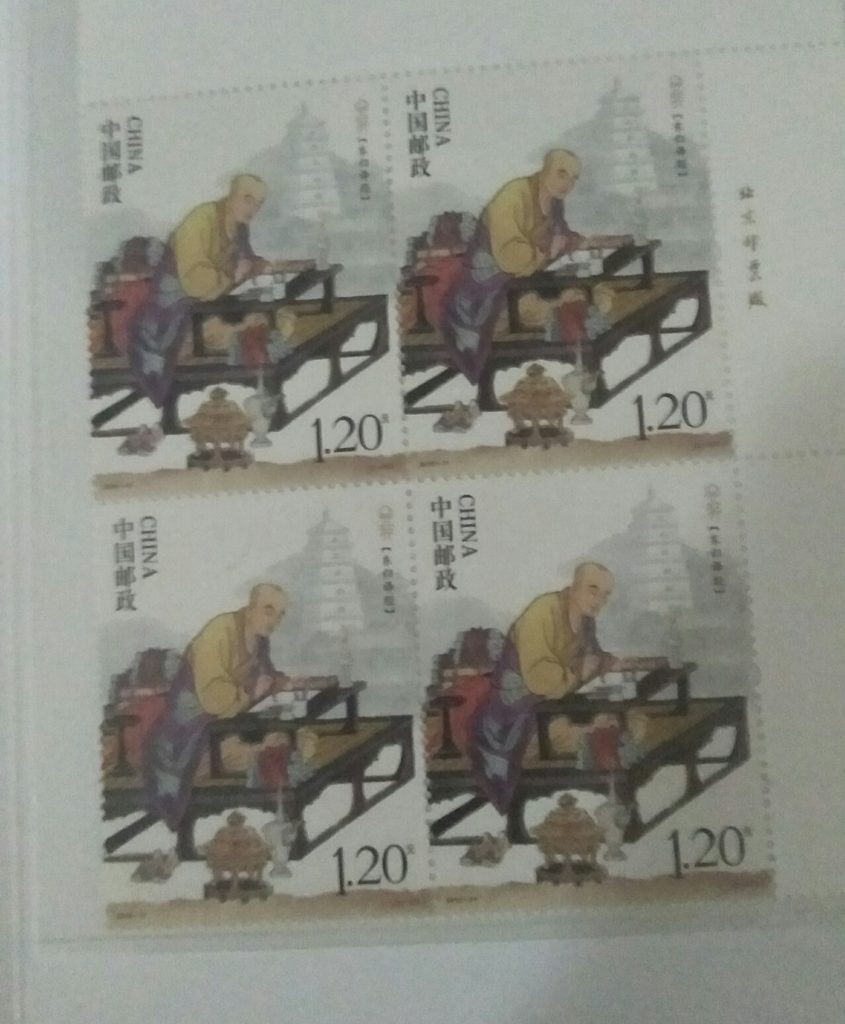

China Philately. This place has all the services of a China Post branch, but they also have display cases of all the recently published collectible sets. As it turns out, stamp collecting has some aspects unique to China. I say this not as a collector myself, but one who has known one my entire life. Micro collections, published as brochures, seem to be more of a thing here than it is in the west. Take this, for example.

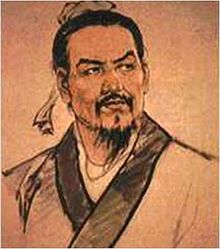

This is a two-fold brochure celebrating Xuan Zang. He’s the Chinese monk who traveled to India to find Buddhist scripture and bring it back to the Middle Kingdom. Famously, this story is told in Journey to the West, a classic that also stars the Monkey King.

Once you open the brochure, you see two sheets of four protected by plastic holders. Since these micro collections act like brocures, there is usually some explanatory text and biographies of the artists involved. As a collectible, it’s not just the stamps themsleves that make this important. The packaging itself is also collectible. So, this isn’t really something where you’d pull the stamps out and put them into a separate album. It’s best to just leave it alone is one complete philatelic item. And that gets into another thing my father has told me, after looking at the stamps I have provided to him in the past.

Chinese stamps are colorful, artistic, and look like a lot of care and attention have been put into their look and design. After all, roughly about one third of global stamp market is made up of Chinese investors. To put it another way, one third of all stamp collectors are Chinese. It’s a big thing in the Middle Kingdom.

To be honest, I am tempted to start collecting myself. My dad would joke that it would have taken him 44 years to convince me that this wasn’t a foolish hobby. Sure, because I have spent much of my adult life talking to my father about postage stamps (I have the collector bug, but it usually was comic books and punk rock vinyl records), I might know more than the average newb. However, for the time being, I think I will just stick with China Philately. I can walk in and point at stuff I want to look at without having to ask complicated questions.

Changzhou has only one of these stores. It’s located dowtown and across the street from the Jiuzhou Shopping Mall.